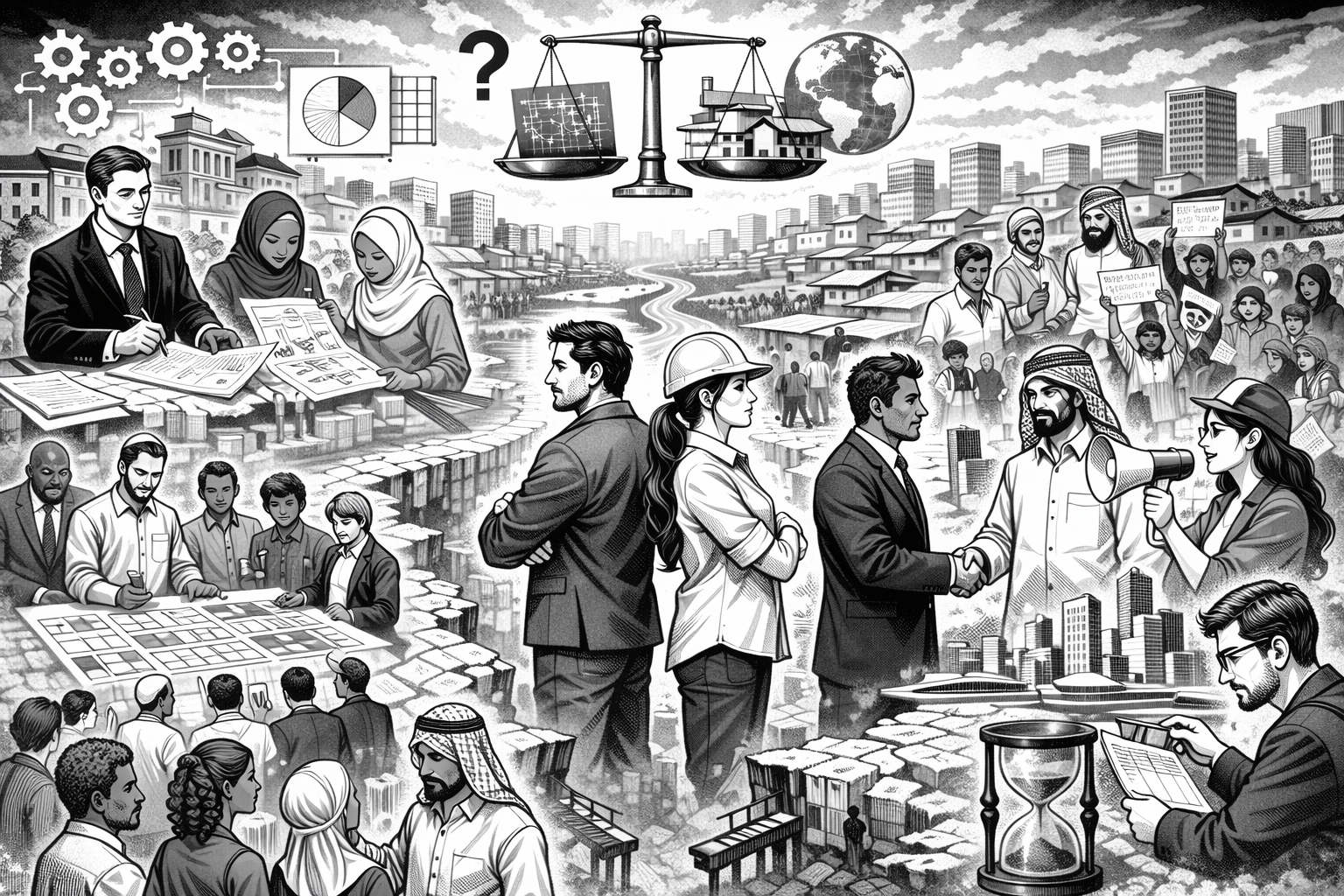

What unites and separates those who plan cities across the world

The great blessing – and sometimes curse – of a globally operating business is that I get the chance to work with urban planners from 20 different countries every single day. You can learn a lot about urban planning when interacting with these great colleagues – and sometimes you wonder…

Urban planning exists everywhere, but it never feels like the same profession twice.

In one place, it is a quiet bureaucratic act: a stamp on a drawing, a paragraph added to a regulation. In another, it is a political gamble, a public fight, or an act of moral courage. Sometimes it is design, sometimes it is law, sometimes it is mediation, sometimes it is little more than hope dressed up as a plan. And yet we keep using the same words—planner, urbanist, urban designer—as if they described a single, stable occupation.

What unites us is not the job description. It is the strange decision to spend a working life dealing with systems too large to fully understand and timelines too long to ever witness. Urban planners choose to care about consequences they will not control and results they may never see. That choice already sets us apart from many other professions.

We work in the space between intention and outcome. A drawing is made; something else gets built. A policy is written; reality finds its loopholes. A public space opens; people use it in ways no workshop predicted. Over time, most planners learn the same lesson, whether in Zurich or Jakarta: cities are not obedient. They negotiate back.

This shared experience creates a quiet global kinship. Planners across cultures recognize the same frustration when good ideas die in committees, the same unease when a project “succeeds” but displaces the wrong people, the same humility that comes from watching informal systems outperform formal ones. We may speak different languages, but we recognize the look of someone who has seen a masterplan unravel.

And yet, the differences between us are fundamental.

Some planners work where rules are strong, budgets reliable, and enforcement expected. Others work where plans are provisional, legality is fluid, and urgency trumps procedure. For some, participation is a structured process with facilitators and minutes; for others, it is a daily negotiation with communities who have learned not to trust official promises. These differences are not cosmetic. They shape how planners think about responsibility, risk, and realism.

There is also a divide in how close we stand to power. In some contexts, planners advise from a distance, careful not to overstep political boundaries. In others, they are instruments of the state—or occasionally its conscience. Urban designers may be invited to imagine bold futures precisely because someone else will deal with the consequences. Urban planners may spend careers managing those consequences without ever being asked to imagine.

Even within the same city, the separation is visible. The planner who writes the regulation rarely meets the designer who gives it form, and neither may talk much to the urbanist who critiques both from the outside. Each sees only part of the city, and each suspects the others of oversimplifying what they themselves know to be complex.

What truly separates us, however, is not role or geography, but belief.

Some planners believe deeply in systems: that better rules, better data, better models will produce better cities. Others believe in agency: that change comes from people, movements, and moments that cannot be planned in advance. Some trust design to lead; others trust governance; others trust adaptation and informality. These beliefs are rarely stated openly, but they guide decisions more than any guideline or framework.

And then there is the question of optimism. In fast-growing cities, planning can feel urgent and necessary, even heroic. In shrinking or overheated cities, it can feel defensive, like damage control. The same profession oscillates between confidence and doubt, between shaping the future and merely trying to soften its blows.

What keeps us connected despite all this is a shared refusal to look away.

Urban planners are people who do not accept the city as a neutral backdrop. We insist that streets, housing, infrastructure, and public space are choices, not accidents. Even when we disagree on what should be done, we agree on this much: the urban condition is made, and therefore can be remade.

That belief is fragile. It is tested daily by markets, politics, climate, and inequality. Many planners carry a quiet sense of failure—not personal, but collective—knowing that the tools available rarely match the scale of the problems faced. And yet, they continue.

Perhaps that is the real profession: not planning cities, but staying engaged with them. Remaining curious in the face of complexity. Accepting that separation—between planner and city, plan and reality, intention and impact—will never fully disappear.

Urban planning is not one global practice. It is a shared question asked in thousands of local dialects: How do we live together, in space, over time?

What unites us is that we keep asking it.