In the vast circus of urban marketing, nothing says exclusivity quite like a definite article. Forget affordability, forget inclusivity — all you need is The.

“The Edge.” – “The One.” – “The Terraces.” – “The Rock.”

One almost expects God Himself to descend from the clouds and cut the ribbon. Instead, it’s usually a developer in a hard hat with a PowerPoint template downloaded from Canva.

Where It All Began: A Branding Trick Turned Gospel

The use of “The” in project names is less architectural than grammatical theatre. In English, “the” signals specificity, uniqueness. There’s not just any river, there is the River. Somewhere along the 1980s and 1990s, when luxury condos sprouted like weeds in North American cities, developers realized that “The” could bestow an air of inevitability. It suggests that this project is not one among many, but the project — the only address worth knowing.

Soon, this virus of grandiosity spread worldwide. Dubai has “The Palm” and “The World” (literal cartographic arrogance). London has “The Shard,” which sounds more like an evil artifact in a Tolkien novel than a place to rent an overpriced flat. Even Beijing has “The Place,” a mall that bravely acknowledges that language has limits.

Developers discovered the power of grammar. Not materials, not design, not affordability. Grammar. And so “The” became a shorthand for aspiration, exclusivity, and thinly veiled segregation.

Dutch Pragmatism Meets “The”

The Netherlands offers a particularly funny case. Traditionally, Dutch developments had charmingly boring names: Vogelbuurt (Bird Neighbourhood), Bloemenbuurt (Flower Neighbourhood), Componistenwijk (Composer’s Neighbourhood). A Calvinist modesty ruled urban branding. Your house might leak, but at least it didn’t try to be glamorous.

Then came global capital. In Amsterdam’s Zuidas district, modesty was banished. Here, English branding and corporate grandeur took over:

- The Edge — A smart office building for Deloitte, advertised as the “greenest in the world.” Translation: a hyper-connected temple for consultants with cappuccino machines.

- The George and The Gustav — Residential towers that sound like failed Eurovision contestants.

- The Rock** — A hulking office block, all sharp lines and jagged façades, named as if it were Dwayne Johnson moonlighting as a developer. In practice, it’s just another granite-and-glass office fortress looming over the financial district.

And let’s not forget Rotterdam, where The Terraced Tower looms over the Maas, a vertical gated community for those who can afford the view.

The irony is almost too much: in a country of bicycles, rain jackets, and pragmatic town planning, housing projects now masquerade as international luxury brands.

What “The” Really Means

The definite article may be tiny, but its urban consequences are large.

“The” is never about the middle class. You don’t get “The Affordable Homes.” You get “The Residences,” “The Lofts,” “The Estates.” The definite article is a velvet rope, telling you this is not for everyone.

Put “The” in front of a project, and suddenly it’s a citadel. The name does the work of a gate, making residents feel like they are special, and ensuring everyone else knows they are not.

And the real kicker? “The” is globally interchangeable. “The Edge” could be in Amsterdam, Austin, or Abu Dhabi. “The One” could be Toronto or Dubai. The branding vocabulary erases cultural context, replacing it with a sterile international language of exclusivity.

A World Tour of “The”

The pilgrimage of “The” takes us around the globe, and the more you look, the more absurdly interchangeable these projects become. In Toronto, there is The One, billed breathlessly as Canada’s tallest condominium tower. Never mind that it looks like every other glass monolith sprouting across the city, its uniqueness resting entirely in the fact that it happens to be slightly taller. The brochures promise a lifestyle of sophistication and grandeur, yet one suspects the most radical act available inside its walls is reheating last night’s pad thai in a built-in microwave.

Fly south to Johannesburg and you find The Leonardo*, Africa’s tallest building. Named, of course, after Leonardo da Vinci, because nothing screams twenty-first-century Johannesburg quite like a Florentine polymath who died in 1519. Here the banality is in the borrowed prestige — as if attaching an Italian Renaissance name to an office-and-apartment tower instantly confers genius on the lift shafts. It is less a building than a branding exercise, a reminder that originality is optional when one can recycle the halo of dead geniuses.

In London, the branding takes a slightly sharper edge — quite literally. The Shard pierces the skyline with a glass spike that architects solemnly describe as a “vertical city.” The marketing suggests it is iconic, but then so does every marketing brochure. In practice, it is a shiny pyramid scheme of office space and overpriced hotel rooms, its claim to fame resting on the fact that it looks pointy. The banality lies in its desperate need to be “iconic” while resembling every other shard of glass shoved into a financial district.

Dubai, of course, has elevated the definite article into performance art. There is The Palm, an artificial island shaped like a palm tree. There is The World, a collection of islands shaped like a badly drawn map of the world. And there is always The Tower, the placeholder name for whichever superlative skyscraper is currently under construction. What appears audacious at first glance quickly dissolves into monotony: each project is little more than a diagram from a child’s colouring book rendered at 1:1 scale. Dubai has discovered that the secret to making global headlines is simply to put “The” in front of basic nouns.

And then there is Beijing, home to the sublimely lazy The Place. It is, indeed, a place — a shopping mall capped with an enormous LED screen roof. No tortured metaphors, no desperate grasp at symbolism, just a straight-faced admission of conceptual bankruptcy. If anything, Beijing’s blunt honesty cuts through the pretension elsewhere. After all, is The Place not the inevitable endpoint of this global branding charade? A mall, a tower, a block of flats — all flattened into the same dreary banality, as if the article itself were doing all the heavy lifting.

What this world tour reveals is not grandeur or uniqueness, but rather how stunningly predictable these projects are. Whether in Toronto, Johannesburg, London, Dubai, or Beijing, “The” offers no innovation. It delivers sameness wrapped in pretension, a linguistic trick designed to hide the fact that what stands before us is little more than yet another glass box, another concrete tower, another mall with slightly shinier tiles. It is the banality of the definite article, repeated across continents, a franchise of mediocrity disguised as destiny.

If Social Housing Used “The”

The absurdity becomes clear if we imagine public housing projects adopting the same strategy. Picture a glossy brochure for The Queue — a fifteen-year wait for a flat you may never get. Or The Basement — student housing with mould included at no extra cost. Perhaps The Last Option — shared flats with paper-thin walls and a boiler that sighs itself to death every winter. The spell only works because “The” signals exclusion. The moment you try to apply it to everyone, the magic vanishes.

Bemused Conclusion: Death by Definite Article

Real estate’s obsession with “The” is both banal and sinister. Banal, because it’s such a cheap trick. Sinister, because it normalizes exclusion through something as small as grammar.

Cities are split into two landscapes:

- The branded enclaves: The Edge, The Rock, The One.

- The unbranded sprawl where everyone else fights for space.

But strip away the brochures, the CGI renderings, the champagne launch parties, and what’s left? A global sameness so profound it almost makes one nostalgic for “Block 14, Section C.” At least that had the honesty of not pretending to be destiny.

Perhaps the next radical development will dare to be honest. Not The Heights, but A Place to Actually Live. Not The Valley, but Some Apartments You Can Afford Without Selling a Kidney.

Until then, we remain governed by the tyranny of the definite article — a tiny word that turns housing into spectacle, cities into franchises, and everyday banality into something sold as The Future.

*P.S.: It turns out that THE Leonardo is not alone. THE Michelangelo is looking at THE Leonardo, soon followed by THE Donatello. Next is probably THE Raphael creating a proper ensemble of THE Ninja Turtles. I am not sure they later will add Splinter, Casey Jones, April O’Neil… – they just don’t have ‘THE’ potential. (thanks for the local context hint Costanza La Mantia, Ph.D.)

** P.S.S.: THE Valley officially is not ‘THE’ but many sources casually added a ‘THE’. Thank you, Gideon Maasland for flagging this up.

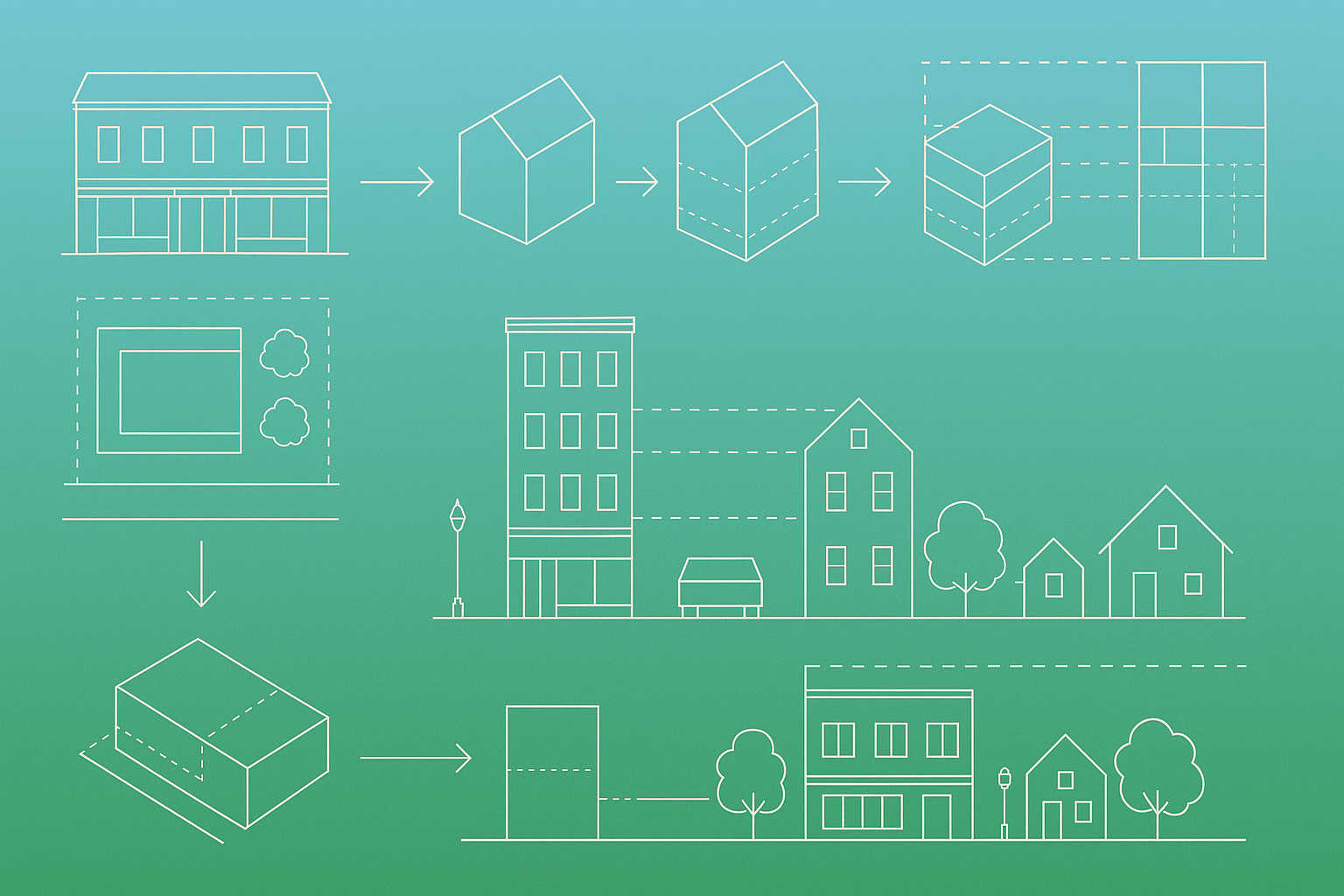

cover image: THE Valley, source: wikimedia.org